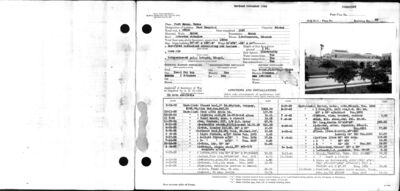

Fort Brown Quartermaster's Ledger

Title

Identifier

1_FBQML-083.jpg

Creation Date

12-26-1941

Description

Building no. 83. Constructed in 1867.

Although the hospital was occupied by 1 May 1869, it was not completed until 1871. It took 1,800 mules, 1,300 civilian employees, and over one million bricks to build the Post Hospital for the Army post. The architectural firm of Bell, Klein and Hoffman, in their Preservation Master Plan for the Old Fort Brown Buildings (1981), observed that three additions appeared to have been made to the hospital. These additions included the two-story tower adjoined to the east wing by a one-story infill and the two-story blocks at the rear. However, a 1869 map shows a “T” form representing the hospital which might indicate that only the far rear block was not present.

Post Inventory and Post Engineers Records of Buildings in Fort Brown are fairly detailed records of expenditures made to repair or upgrade post buildings that include photographs and floor plans. Every building has a numbered designation. The Post Hospital is Building No. 83 and its walls have a thickness of twelve inches. Sections will, hereupon, be referenced to by letters A through G to denote each section of Gorgas Hall (see floor plan) Section A, the west wing nearest May Street and C, the opposite wing to the east, were the main wards of the building. A 1962 article in The Brownsville Herald stated that Fort Brown assistant surgeon William J. Wilson reported in 1870 that the hospital had accommodations for twenty-four beds. By 1938 three offices and the dispensary occupied the floor. Two rooms near the front entrance were used by orderlies, with a surgery office and dispensary to the rear by 1941. The second floor of section B was divided into separate wards for officers and prisoners with a single 13’ x 13’ holding cell.

Photographs by Robert Runyon during the early 1900s show that Section D, now an office for Administration and Partnership Affairs, was an open-arched passageway during the early 1900s. Quartermasters' records from 1921 to 1941 list this section as being divided into an x-ray and operating room, with the first floor of the connected Section E divided into a sterilization room, x-ray dark room (with a boiler room inserted in between by 1938), and operating room in front. In 1936, the second floor included a pathology lab, but was used exclusively as the dentist’s office with two operating rooms, various small rooms, and a waiting room thereafter. The first floor of Section F behind the main central block was a 12’ x 31’ dining area, with an obstetrical ward on the second floor. At the rear (Section G) were the kitchen and store rooms on the first floor, with a day room and toilet on the second floor. Sections D, E, and G probably existed by 1871.

In 1976, Ruby A. Wooldridge, best remembered for teaching at Texas Southmost College and her book, Brownsville: A Pictorial History with Robert B. Vezzetti in 1982, stated in an unpublished history of Texas Southmost College that Brownsville Junior College (later TSC) made major renovations in September 1948, and the post hospital building was converted to house:

The science laboratories, art department, college library, permanent offices of the Dean and registry, science lecture rooms, office of the superintendent of the grounds, journalism department and the faculty lounge. The room on the second floor of the former hospital, which had been used by the army for confining violent patients, was used jointly by the Junior College and the Brownsville Historical Society for the storage of rare books and documents.

A 1949 Sanborn Map indicates sections A and G were used as classrooms, B as offices, C as a library, and E as study rooms. A 1971 TSC Bulletin states the “Gorgas Science Center” was remodeled to include three biology laboratories [in sections C and E] with imminent plans for Science, Mathematics, and Engineering labs. By 1972, Gorgas was mainly an administrative building with the completion of Eidman Hall as a science building By 1981, Gorgas housed the Offices of the President and Vice-President, Registrar’s, Veteran’s Affairs, Business and the Counseling Center.

The task of keeping Gorgas (and other historical buildings) in pristine condition has been tested by time and trial. Although remodeling the interiors suited academic needs, undoing the mistakes of well-intended caretakers and the elements of nature began a program of continual restoration efforts of upkeep of the buildings. By 1991, the retransformation of old buildings was complete, thanks to a 1986 $13.5 million bond issue approved by voters to boost the college’s growth and rescue historical buildings from further debilitation. TSC was presented with a plaque by the Brownsville Historical Association for its efforts to preserve historic fort buildings and for making the Post Hospital a National Historic Landmark in Texas

Nearly every building on campus is enhanced by arches of one form or another. Architectural features that stem from Gorgas Hall give UTB/TSC an unprecedented uniqueness among other colleges. In 1993, the Architecture and Design Review of Houston magazine included a booklet, “On the Border: An Architectural Tour,” featuring Brownsville buildings in which the design of the Gorgas building was noted for its “brick arches, brick pilasters and brick corbeling at the roof line -- [as being] redolent of the Creole architectural tradition of Northeastern Mexico.”

This section of the Post Hospital will be finalized by retelling a story from the Brownsville Herald about Dr. William Crawford Gorgas, beginning with his thirty-year battle at the age of twenty-seven against Yellow Fever, Yellow Jack, or vomito negro as it was known in Mexico. He arrived at Fort Brown in 1882, amidst the epidemic which overtook its victims with body aches, fever, and nausea that induced black vomit. Freshly dug graves stood open and ready to swallow another victim and their belongings. The dreaded disease was known to have “wiped out entire armies and thousands of civilians in tropical climates in the western hemisphere.” One case involved the invading American Army of Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1846 and another, when the Spanish Army was rendered impotent by Yellow Fever in its attempts to suppress Cuban insurrectionists in the 1890s. A “study” suggested that Spanish Conquistadors brought it over with African Negroes. In Brownsville, some blamed carriers to have been railroad workers from Tampico or seamen from New Orleans. Lieutenant Gorgas was instructed by his colleagues to carry whiskey, brandy, mustard seed and cigars to help ward off the disease as no cure was known. Also unknown was that the mosquito was to blame for carrying the virus. It was thought the disease was transmitted through personal contact, filth from streets or marshes, or the putrid odor in the atmosphere that rose from this filth. Gorgas began dissecting bodies in the “dead house,” as the Old Morgue was then called, to study the cause of Yellow Fever. He had been ordered to stay away from patients and was briefly arrested for disobeying those orders.

Because it was not known how the fever spread, a Yellow Fever doctor was also relegated to being undertaker, grave digger and clergyman. One night, following his experience at Fort Brown, Dr. Gorgas described to colleagues at Fort Barranca, Florida, the horrible details of what is was like to dig a grave, wrap a corpse in a white shroud, add quick lime to an empty coffin before placing the corpse within it, the internment “and the reading of the burial service by the light of a lantern.” One cannot imagine what went through his mind when one day as he looked into an open grave of the National Cemetery on the island and was asked by another doctor to read a burial service for Miss Marie Cook Doughty, whose drawn-out, fifteen-day illness made it seem as her time would come very quickly. He agreed, too, but continued to treat her.

To Miss Doughty, he was the “Gorgeous Doctor” and when he would come visit her in the cool dark of night, she could hardly see his face, but was lulled by the “musical tones of his voice and his soft southern accent.” His treatment of her and subsequent illness beside her resulted in a lifelong partnership in which she accompanied him in his pursuit to stamp out Yellow Jack for good. Both became immune following their recovery and when it was theorized that the stegomyia mosquito was the enemy, Dr. Gorgas began warfare to eradicate the mosquito. Some of his quarantine methods included the elimination of stagnant water, the insects’ breeding grounds, and fumigation techniques. Oil was also poured into marshes. His campaign against the epidemic took him to Panama where the construction of the canal had been interrupted by the disease. By 1914, he was appointed Surgeon General of the Army. While in London in 1920 to meet King George V, Dr. Gorgas had a cerebral hemorrhage. The king visited him in the hospital and at length expressed his sincere appreciation for the work he did for humanity. Gorgas died on July 4, 1920 and is credited with proving the mosquito carried the disease and finding ways to eliminate it. His efforts virtually eliminated yellow fever. A memorial plaque was placed on the Fort Brown hospital building presented in a ceremony by the Brownsville Historical Association (BHA) and Brownsville Junior College to commemorate Gorgas in February 1949. Later that same year the BHA, in conjunction with other organizations, were able to have Gorgas elected to the Hall of Fame. Gorgas Drive and the TSC’s Gorgas Science Foundation also bear the name of the doctor.

Its arches, pilasters, denticulated cornices, and other decorative brickwork are the result of innovative building practices imported from Spain to Mexico that made their way into architecture along the Rio Grande River. The drawing below exemplifies the architectural elements that make this building much more remarkable then what it might have been if it had not been altered from standard Army building plans by William A. Wainwright and Samuel W. Brooks.

Physical Description

.JPG, 1 Page, 26 x 35 cm

Preview

Recommended Citation

Fort Brown Quartermaster's Ledger, Texas Southmost College, UTRGV Digital Library, The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley. Accessed via https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/ftbrown/

Some files may download without file extensions. Please add '.jpg' to the end of the filename to open the file.

Keywords

Texas--Fort Brown, Texas--Brownsville, 1860-1869, 1920-1929, 1930-1939, 1940-1949, Military camps, Military hospitals, Records (Documents), Architectural drawings